Nettuts+ Updates - 14 Reasons Why Nobody Used Your jQuery Plugin

|

14 Reasons Why Nobody Used Your jQuery Plugin Posted: 07 May 2012 03:45 AM PDT With so many folks developing jQuery plugins, it’s not uncommon to come across one that just plain – for lack of better words – sucks. There’s no examples or documentation, the plugin doesn’t follow best practices, etc. But you’re one of the lucky ones: this article will detail the pitfalls that you must avoid. jQuery is no stranger to those of you frequent Nettuts+. Jeffrey Way’s awesome 30 Days to Learn jQuery (and various other tutorials here and elsewhere) have led us all down the path to Sizzle-powered awesomesauce. In all the hype (and a lot of leaps in JavaScript adoption by developers and browser vendors), plenty of plugins have come onto the scene. This is partially why jQuery has become the most popular JavaScript library available! The only problem is that many of them aren’t too great. In this article, we’ll focus less on the JavaScript specifically, and more on best practices for plugin delivery. 1 – You Aren’t Making a jQuery PluginThere are some patterns that are, more or less, universally accepted as “The Right Way” to create jQuery plugins. If you aren’t following these conventions, your plugin may… suck! Consider one of the most common patterns:

(function($, window, undefined){

$.fn.myPlugin = function(opts) {

var defaults = {

// setting your default values for options

}

// extend the options from defaults with user's options

var options = $.extend(defaults, opts || {});

return this.each(function(){ // jQuery chainability

// do plugin stuff

});

})(jQuery, window);

First, we are creating a self-invoking anonymous function to shield ourselves from

using global variables. We pass in

Passing the variable for the globally accessible

Next, we are using the jQuery plugin pattern,

$.PluginName = function(options){

// extend options, do plugin stuff

}

This type of plugin won’t be chainable, as functions that are defined as properties of the jQuery object typically don’t return the jQuery object. For instance, consider the following code:

$.splitInHalf = function(stringToSplit){

var length = stringToSplit.length;

var stringArray = stringToSplit.split(stringToSplit[Math.floor(length/2)]);

return stringArray;

}

Here, we are returning an array of strings. It makes sense to simply return this as an array, as this is likely what users will want to use (and they can easily wrap it in the jQuery object if they wish). In contrast, consider the following contrived example:

$.getOddEls = function(jQcollection){ //

return jQcollection.filter(function(index){

var i = index+1;

return (index % 2 != 0);

});

}

In this case, the user is probably expecting the jQuery object to return from 2 - You Aren’t Documenting Your Code (Correctly)Arguably, the most important thing you can do when publishing your code is add the necessary documentation. The gap between what you explain to developers and what the code actually does or can do is the time that users don’t want to waste figuring out the ins and outs of your code. Documentation is a practice that doesn’t have any hard-fast rules; however, it is generally accepted that the more (well organized) documentation you have, the better. This process should be both an internal practice (within/interspersed throughout your code) as well as an external practice (explaining every public method, option, and multiple use cases thoroughly in a wiki or readme). 3 – You Aren’t Providing Enough Flexibility or CustomizabilityThe most popular plugins offer full access to variables (what most plugins refer to as “options” objects) that a user may want to control. They also may offer many different configurations of the plugin so that it is reusable in many different contexts. For instance, let’s consider a simple slider plugin. Options that the user might wish to control include the speed, type, and delay of the animation. It’s good practice to also give the user access to classnames/ID names which are added to the DOM elements inserted or manipulated by the plugin. But beyond this, they may also want to have access to a callback function every time the slide transitions, or perhaps when the slide transitions back to the beginning (one full “cycle”).

Let’s consider another example: a plugin that makes a call to an API should provide access to the API’s returned object. Take the following example of a simple plugin concep:.

$.fn.getFlickr = function(opts) {

return this.each(function(){ // jQuery chainability

var defaults = { // setting your default options

cb : function(data){},

flickrUrl : // some default value for an API call

}

// extend the options from defaults with user's options

var options = $.extend(defaults, opts || {});

// call the async function and then call the callback

// passing in the api object that was returned

$.ajax(flickrUrl, function(dataReturned){

options.cb.call(this, dataReturned);

});

});

}

This allows us to do something along the lines of:

$(selector).getFlickr(function(fdata){ // flickr data is in the fdata object });

Another way of publicizing this is to offer “hooks” as options. As of

jQuery 1.7.1 and up, we can use

$.fn.getFlickr = function(opts) {

return this.each(function(i,el){

var $this = el;

var defaults = { // setting your default options

flickrUrl : "http://someurl.com"; // some default value for an API call

}

var options = $.extend(defaults, opts || {});

// call the async function and then call the callback

// passing in the api object that was returned

$.ajax(flickrUrl, function(dataReturned){

// do some stuff

$this.trigger("callback", dataReturned);

}).error(function(){

$this.trigger("error", dataReturned);

});

});

}

This allows us to call the

$(selector).getFlickr(opts).on("callback", function(data){ // do stuff }).on("error", function(){ // handle an error });

You can see that offering this kind of flexibility is absolutely important; the more complex actions your plugins have, the more complex the control that should be available. 4 – You’re Requiring Too Much ConfigurationOk, so tip number three suggested that the more complex actions your plugins have, the more complex control that should be available. A big mistake, however, is making too many options required for plugin functionality. For instance, it is ideal for UI based plugins to have a no-arguments default behavior. $(selector).myPlugin(); Certainly, sometimes this isn’t realistic (as users may be fetching a specific feed, for instance). In this case, you should do some of the heavy lifting for them. Have multiple ways of passing options to the plugin. For instance, let’s say we have a simple Tweet fetcher plugin. There should be a default behavior of that Tweet fetcher with a single required option (the username you want to fetch from).

$(selector).fetchTweets("jcutrell");

The default may, for instance, grab a single tweet, wrap it in a paragraph tag, and fill the selector element with that html. This is the kind of behavior that most developers expect and appreciate. The granular options should be just that: options. 5 – You’re Mixing External CSS Rules and Inline CSS RulesIt’s inevitable, depending upon the type of plugin, of course, that you will have to include a CSS file if it is highly based on UI manipulations. This is an acceptable solution to the problem, generally speaking; most plugins come bundled with images and CSS. But don’t forget tip number two – documentation should also include how to use/reference the stylesheet(s) and images. Developers won’t want to waste time looking through your source code to figure these things out.

With that said, it is definitely a best practice to use either injected styles (that are highly accessible via plugin options) or class/ID based styling. These IDs and classes should also be accessible, via options as previously mentioned. Inline styles override external CSS rules, however; the mixing of the two is discouraged, as it may take a developer a long time to figure out why their CSS rules aren’t being respected by elements created by your plugin. Use your best judgment in these cases.

6 – You Don’t Offer ExamplesThe proof is in the pudding: if you can’t provide a practical example of what your plugin does with accompanying code, people will quickly be turned off to using your plugin. Simple as that. Don’t be lazy. A good template for examples:

7 – Your Code Doesn’t Match Their jQuery Version

jQuery, like any good code library, grows with every release. Most methods are kept

even after support is deprecated. However, new methods are added on; a perfect example

of this is the

8 - Where’s the Changelog?

Along with keeping your jQuery version support/compatibility a part of your documentation, you should also be working in version control. Version control (specifically, via GitHub) is largely the home of social coding. If you are developing a plugin for jQuery that you want to eventually publish in the official repository, it must be stored in a GitHub repository anyway; it’s time to bite the bullet if you haven’t learned how to use version control. There are countless benefits to version control, all of which are beyond the scope of this article. But one of the core benefits is that it allows people to view the changes, improvements, and compatibility fixes you make, and when you make them. This also opens the floor for contribution and customization/extension of the plugins you write. Additional Resources

9 – Nobody Needs Your Plugin

Ok, we’ve ignored it long enough here: some “plugins” are useless or too shallow to warrant being called a plugin. The world doesn’t need another slider plugin! It should be noted, however, that internal teams may develop their own plugins for their own uses, which is perfectly fine. However, if you’re hoping to push your plugin into the social coding sphere, find a reason to write more code. As the saying goes, there’s no reason to reinvent the wheel. Instead, take someone else’s wheel, and build a racecar. Of course, sometimes there are new and better ways of doing the same things that have already been done. For instance, you very well might write a new slider plugin if you are using faster or new technology. 10 – You Aren’t Providing a Minified VersionThis one is fairly simple: offer a minified version of your code. This makes it smaller and faster. It also ensures that your Javascript is error free when compiled. When you minify your code, don’t forget to offer the uncompressed version as well, so that your peers can review the underlying code. Free and cheap tools exist for front-end developers of all levels of experience.

11 – Your Code is Too CleverWhen you write a plugin, it is meant to be used by others, right? For this reason, the most effective source code is highly readable. If you’re writing countless clever one-liner lambda style functions, or your variable names aren’t semantic, it will be difficult to debug errors when they inevitably occur. Instead of writing short variable names to save space, follow the advice in tip number nine (minify!). This is another part of good documentation; decent developers should be able to review your code and understand what it does without having to expend too much energy.

Additionally, if you find yourself consulting documentation to remember what your own strange looking code is doing, you also likely need to be less concise and more explanatory. Restrict the number of lines in each function to as few as possible; if they stretch for thirty or more lines, there might be a code smell. 11.You Don’t Need jQueryAs much as we all love using jQuery, it is important to understand that it is a library, and that comes with a small cost. In general, you don’t need to worry too much about things like jQuery selector performance. Don’t be obnoxious, and you’ll be just fine. jQuery is highly optimized. That said, if the sole reason why you need jQuery (or a plugin) is to perform a few queries on the DOM, you might consider removing the abstraction entirely, and, instead, sticking with vanilla JavaScript, or Zepto.

13 – You’re Not Automating the Process

Grunt is a “task-based command line build tool for JavaScript projects”, which was covered in detail recently here on Nettuts+. It allows you to do things like this: grunt init:jquery This line (executed in the command line) will prompt you with a set of questions, such as the title, description, version, git repository, licenses, etcetera. These pieces of information help to automate the process of setting up your documentation, licensing, etc. Grunt does far more than just make some customized boilerplate code for you; it also offers built in tools, like the code linter JSHint, and it can automate QUnit tests for you as long as you have PhantomJS installed (which Grunt takes care of). This way, you can streamline your workflow, as tests run instantly in the terminal on save. 14 – You’re Not TestingOh, by the way – you do test your code, right? If not, how can you ensure/declare that your code works as expected? Manual testing has its place, but, if you find yourself refreshing the browser countless times every hour, you’re doing it wrong. Consider using tools, such as QUnit, Jasmine, or even Mocha. Testing is particularly useful when merging in pull requests on GitHub. You can require that all requests provide tests to ensure that the new/modified code does not break your existing plugin.

Some Helpful ResourcesWe wouldn’t be doing you any favors by just telling you what you’re doing wrong. Here are some links that will help get you back on the right path!

Closing ThoughtsIf you are writing a jQuery plugin, it is vital that you stray away from the pitfalls listed above. Did I miss any key signs of a poorly executed plugin? |

|

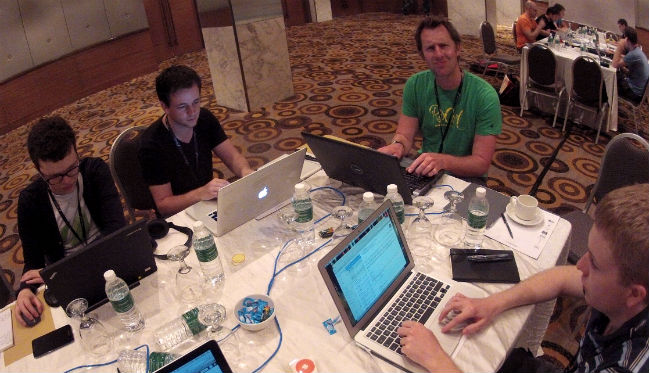

Posted: 06 May 2012 05:20 PM PDT Each month, we bring together a selection of the best tutorials and articles from across the whole Tuts+ network. Whether you’d like to read the top posts from your favourite site, or would like to start learning something completely new, this is the best place to start! We’ve Been in Kuala Lumpur!This month we’ve been attending an Envato company meet-up in Malaysia. We’ve had a fun time working together as a team, made lots of exciting plans for the future of Tuts+, and also had the chance to meet up with lots of our readers! Thanks to everyone who took the time to attend our community meet-up and, if you’re interested, you can find out a bit more about our trip here (and see a few photos!)  Psdtuts+ — Photoshop Tutorials

Nettuts+ — Web Development TutorialsVectortuts+ — Illustrator TutorialsWebdesigntuts+ — Web Design TutorialsPhototuts+ — Photography TutorialsCgtuts+ — Computer Graphics TutorialsAetuts+ — After Effects TutorialsAudiotuts+ — Audio & Production TutorialsActivetuts+ — Flash, Flex & ActionScript TutorialsWptuts+ — WordPress TutorialsMobiletuts+ — Mobile Development Tutorials |